'De-Extinctionist' Discusses Relationships with Other Scientists and the Public, by Taylor Morris

In his efforts to bring extinct species back to life, Professor Michael Archer, PhD believes fostering cooperation and dialogue among different branches of biology and with general audiences interested in science research.

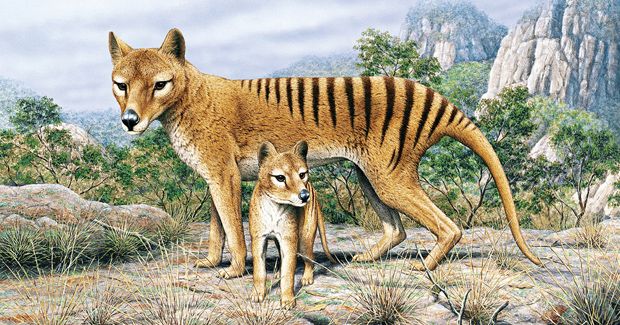

Archer, who teaches at the University of New South Wales’s School of Biological, Earth, and Environmental Sciences in Sydney, Australia, has been involved in reviving the Tasmanian Tiger, or thylacine, a marsupial that went extinct in 1936. He is also working on the Lazarus Project, his effort to revive the gastric brooding Frog, a more recently extinct species that curiously gave birth by burping up its young from its stomach after temporarily ingesting the eggs. But while he has worked in de-extinction for decades, Professor Archer says he began to make connections with others in this area of study only during a Washington D.C. conference on de-extinction in March of last year.

“Until the Revive & Restore group and the National Geographic Society asked me if I would talk in Washington in 2013…I was blissfully unaware of all the other people around the world who had similar visions of trying to bring back extinct animals from nearly every continent on earth,” he said.

Archer says the conference established many of the relationships de-extinction scientists have with each other, providing new opportunities for research.

“A lot of us developed friendships around that room in 2013 that we never would’ve anticipated. We’ve begun to collaborate in one of our projects, in the Lazarus Project, with Bob Lanza and people in advanced cell technology who got excited about what we’re doing. So it’s been very useful to meet all these people and discover that maybe some of them have ideas about how everyone else can solve some of the problems that they’re dealing with,” he said.

Although no extinct animals have been revived yet “de-extinctionists” are working on bringing back a great variety of species, from Archer’s gastric brooding frog in Australia, to the passenger pigeon in the United States, to the Pyrenean ibex in Spain. Archer believes that each one of these diverse ventures is both well-reasoned and worthy and claims this view is broadly shared among the de-extinctionist community.

“When I was in Washington and around the table with probably about 30 other people involved in projects of all kinds that could be broadly described as de-extinction projects, I didn’t hear one discussion that caused me to be other than excited about the possibility of a positive outcome in relation to their projects,” he said, adding “I haven’t seen anyone being critical of anyone else’s project. I think we’re all struggling against a darkness that’s beginning to sweep across the world, and everybody hopes that everybody else is successful in their small way in trying to slow down this avalanche of extinctions and maybe get a few back that we never should have lost in the first place.”

Despite the unity and mutual support among de-extinctionists, Archer acknowledges that conservation scientists have not always welcomed efforts to revive extinct species.

“There certainly is some disquiet in some sectors of the scientific community about what it would mean if we could actually demonstrate that we can bring an extinct animal back to life. Some ecologists are frightened that in effect what we will have done is extinct the idea of extinction, and in doing that, they worry that the rest of the world—that certainly includes many people very concerned about conservation of endangered species today—will lose relative interest in persisting with those programs to help living species to not go extinct, because we will have demonstrated that it’s not a big deal if they go extinct; we can bring them back,” he said.

Archer argues, however, that these concerns from conservationists are overblown, because the donor bases for conservation and de-extinction efforts are essentially separate.

“In my experience, the resources that are funding de-extinction projects, including, for example, our Lazarus Project, are coming from people who are not otherwise supporting conservation. They are supporting the de-extinction projects because they’re fascinated about the technology. The idea of possibly being able to bring back an extinct species has had them putting their hand in their pocket for the first time about anything to do with an animal on the planet. So I don’t think we’re talking about any risk of undermining resources or support for…concern about living species,” he said.

Archer considers conservation scientists natural allies with de-extinctionists, whose research might also be used to prevent the potential loss of more species.

“The techniques that we’re developing—and that many of us are having to rely on—are going to be increasingly important in increasing the efficiency of modern conservation projects focused on endangered living species. So I see these as compatible strategies, compatible efforts. De-extinction is just one tool that all of us have—and are trying to develop—to increase the efficiency of what everybody else is trying to do: to optimize global biodiversity, genetic biodiversity,” he said.

In particular, Archer discusses somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) as a tool de-extinctionists are using and refining that will help with conservation efforts. The technique involves transferring body cell nuclei into enucleated egg cells to create an embryo. De-extinctionists hope to use SCNT to transfer the nuclei of extinct species into the egg cells of closely-related species and then use members of those related species as surrogate mothers to bring back the extinct species. Developing this technique for de-extinction, Archer claims, could also aid in supplementing the breeding capacity of endangered species, whose body cell nuclei could also be transferred to the enucleated eggs of close living relatives, which could then birth the endangered species.

Archer sees sharing techniques from other branches of biology as essential to the success of de-extinction projects. Specifically, Archer mentions borrowing concepts from synthetic biologists, who work on altering the traits of living species, as opposed to bringing back species that have gone extinct.

“I think that synthetic biology offers one of the most important tools to the de-extinction biologists in being able to address what may be the cause of the extinction in the first place and get around that problem, for example in the Lazarus Project, which in our case is focused on the Australian gastric brooding frog. Like many frogs around the world, we suspect the reason it’s extinct is the Chytrid fungus…this Chytrid fungus was spread around by people taking the African clawed frog for use in human reproductive activities everywhere outside of Africa, and we think that frog is responsible, with human help here, for spreading the Chytrid Fungus on every continent on the planet. It is now clear that some frog populations that haven’t completely succumbed to the spread of this fungus have shown individuals that have developed genes that seem to confer immunity to them in those populations,” he said.

Archer continued, “Now, once we can discover that, there’s no reason why we can’t synthetically sequence the same sequence…and actually insert it into the gastric brooding frog. If we can get that frog back, before we put it back into its habitat, which still exists, I think it would be in ou[r] and the frog’s very critical interest in insuring that it was resistant to the same fungus that took it out in the first place. So I think synthetic biology is going to be one of the most important powerful tools in the whole de-extinction process.”

Archer says the frog, which can essentially turn its stomach into a uterus to birth its young orally, would be of great interest to medical researchers, because it is able to suppress its stomach’s gastric juices to avoid destroying its eggs.

However, Archer believes that relationships with the public are just as important as these burgeoning connections with other scientists. He worries that the public lacks truly informative science programming and sees scientists as responsible for ensuring that general audiences are not deceived by what he calls the “sensationalism” promoted in popular science media and television.

“I think that the problem the public has is a very real one. They’re confronted with programs of all kinds that are getting even more and more bizarre today, and it must get harder and harder for the person without a scientific education to know whether they should believe what they’re hearing or not. And that does, therefore, make it incumbent upon the scientists themselves not to churn out more scientific stuff… but to recognize that the capacity of the average member of the public to absorb scientific ideas is relatively limited and to deliberately present explanations of what they’re doing and why in a language, frankly, that the average ten year old would have no trouble embracing. I try to do this, and in all my PhD students I regard this to be a critical skill that we teach them,” he said.

Though some still resist interaction with the public, Archer claims that general interest in their work and, increasingly, desire for generous grant funding, are requiring scientists to become more engaged with media and non-scientists.

He continued, “[Y]ou’ll still find many scientists who feel that they shouldn’t have to justify what they’re doing, they should be able to sit in their academic ivory towers, do their research, and it’s really nobody’s business but theirs. But increasingly, that’s demonstrably not the case, and I think on every continent on earth, scientists are recognizing, among other things, that the public is interested in what they’re doing, does want to know what they’re doing, and maybe for more practical considerations, the funding bodies that provide research funds for a range of research activities are increasingly looking at whether or not the person they’re funding or the research team they’re funding is, in fact, doing something that they’re going to be happy to see on the front pages of the newspaper, and, even more, something that people in that team will continually explain to the public about why it’s exciting and why the results that they’re getting are important and what it’s going to mean. And that’s becoming a bigger and bigger factor in funding bodies’ decisions about whether or not they fund individual research projects.”

In his own media appearances, Archer hopes that he will help audiences recognize the importance of challenging assumptions about what is or is not possible in science in order to make improvements to the earth’s biological health.

Archer concluded, “Too often, I hear scientific colleagues teaching students about what’s impossible, what we can’t do. And if there’s one message that I try to get through to students and the public it is for goodness’ sake, don’t accept what can’t be done. When somebody tells you something is impossible, that should be a red flag to question whether or not you might be able to do it anyway… It’s the message that de-extinction is really putting in front of the world. De-extinction was ‘impossible,’ and we have a mantra, ‘extinction is forever.’ Well, is it? And if it isn’t, then why on earth wouldn’t we try to see if it’s possible to increase the viability of global ecosystems with this process? So I guess… that’s my main message: don’t believe people when they tell you something can’t be done. That’s the quickest and most exciting invitation to see if they’re wrong.”