Ezra Furman Is Doing What She Wants

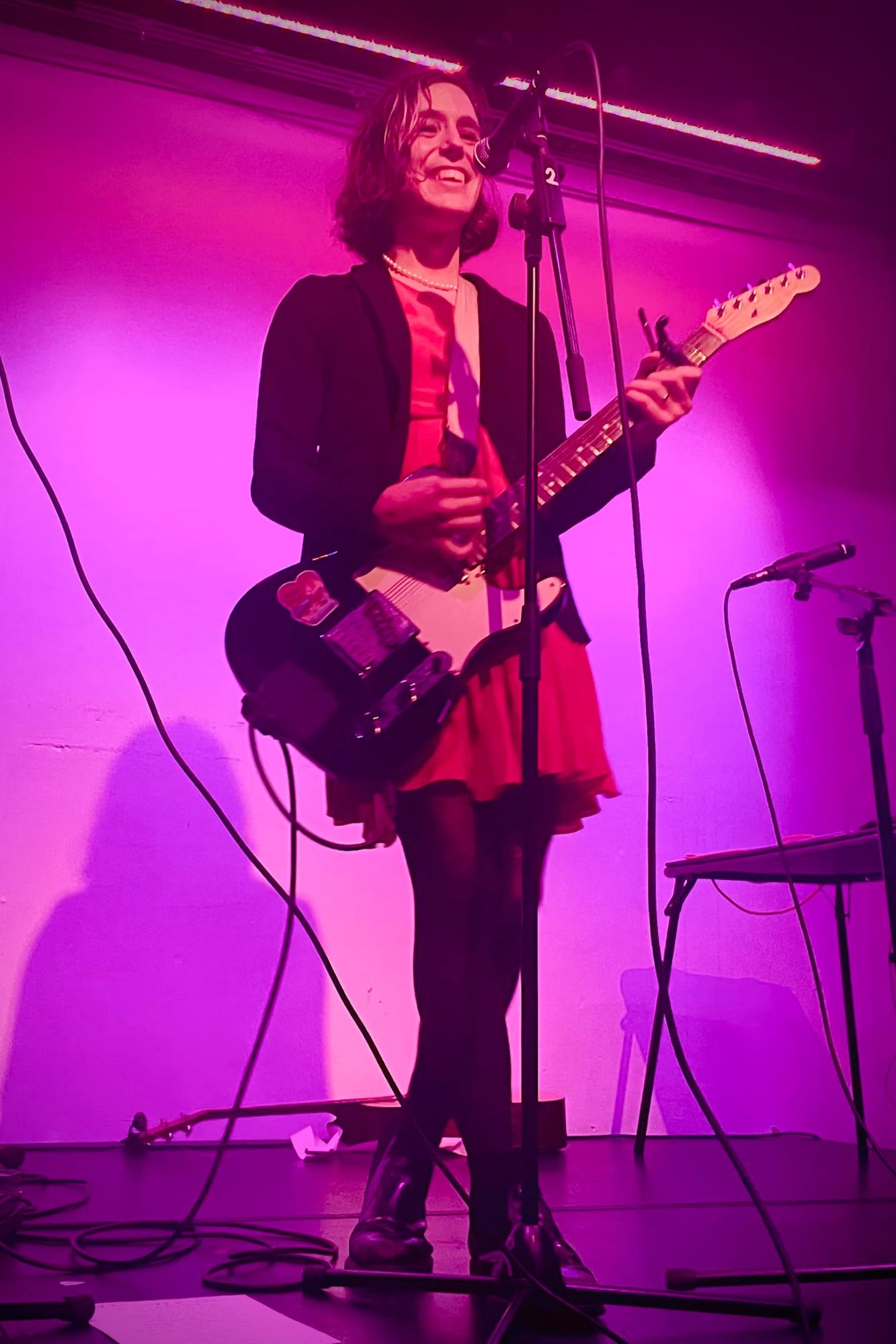

// Image by Journey Whitney

You can often spot Ezra Furman by her vibrant red clothing, usually a coat. She mingles with friends and fans — audiences of fewer than a hundred people — and watches her openers’ sets from the seats. She takes the stage with a reserved yet dignified air. Her monthly performances at the Rockwell for the past half year have all started roughly the same way, but each takes off in their own direction soon after. Returning showgoers have something new to look forward to in every installment of “Ms. Ezra Furman doing what she wants,” as she calls it. As alluded to by the title, the setlists are variable and subject only to Furman’s whims. She does not limit herself to just her own music, frequently featuring covers such as “Ventura” by Lucinda Williams, “Woman of a Calm Heart” by Ilene Weiss, and “Candy Says” by The Velvet Underground, which she performed as a duet with Alex Walton.

Writing about exactly what goes on during these performances is difficult because it almost feels like betraying a secret. It’s like an initiation ritual you have sworn not to discuss with outsiders — all you can do is insist they experience it for themselves. At the very least it must be emphasized that Ezra Furman is a sight to behold. If I didn’t know any better, I might have described her as meek from her speaking voice, but as soon as she has a guitar in her hands, she doesn’t need the microphone in order for the whole venue to hear her.

The audience listens to and participates in the dialogue Furman facilitates through her music. They resonate with the energy of fan favorites like “Love You So Bad” and more niche picks like “Temple of Broken Dreams” and “Maraschino-Red Dress $8.99 at Goodwill.” She doesn’t take requests, so you can’t count on hearing any one song in particular regardless of its popularity. I, like the rest of the crowd,am just happy to be here and experience raw emotions with others. “Songs invite out certain feelings,” Furman said during her December performance. “And some of us need our feelings invited out.”

The pseudo-residency continues with shows on February 6, March 5, and April 10 at the Rockwell in Davis Square.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Journey Whitney: So, you’ve announced your next three shows in the “Ms. Ezra Furman doing what she wants” series.

Ezra Furman: Yeah. These shows, I think they’re good for me as an artist. I can’t not make any money, so it’s good for that reason ... but I gotta tell you, I’m in some kind of post-career moment. I just feel like my career is over, and that’s good because I can do art now.

Do you think that’s related to Sex Education being over?

Yeah. And, you know, I made nine LPs — they’re really three trilogies. It helps me to think of it like an era ending. I got a little burned out on hustling for everyone’s attention all the time and telling everyone, “Hey, look at me! Buy stuff from me!” I don’t know if I can really do it anymore. I’m on hiatus from touring, and there’s a few practical reasons, but it’s a deep spiritual change that it represents for me.

Do you feel like you came out of that hustle successful? Would you consider yourself a successful person? Does that matter?

I don’t know. We’re shown pictures of famous people all day, and I’m like, “Oh my God, I’m so lucky to not be famous.” I used to really want to be hyper-famous, and I’m so relieved that didn’t happen. It could have, I dodged a bullet. It seems hellish. If I’m gonna be an entertainer, I feel like I gotta be just a little bit famous. I really like the amount of fame that I have. I’ve got my little business. I don’t have to think so hard about it. To be honest, profit is never a big motivator for me, except when I go on tour. My job now is to be for real, you know? And do spiritual growth.

It’s not time for another album. No one’s asking for it — that’s what I always feared. I remember when I first made a record, my first album with my college band The Harpoons, I was like, “I never want to make an album just because it’s time to make an album.” I don’t really think this way anymore, but there’s something to it. I wanted it to arise organically. I wanted to make art.

You know what I did today? I recorded a cassette tape. Well, I started a while ago. I finished recording on the same cassette tape all the songs that I wrote in 2023.

How many songs was that?

It was a paltry 10 songs. For me, that’s really not very much. I used to be frustrated if I went a whole week without writing a song, but that was long ago. I think these songs are a lot better than those songs I used to write when I was doing a song a week. I let them arise of their own accord a little more. Didn’t follow every idea, just the ones that really got their hooks in me.

What kind of ideas have gotten their hooks in you?

I noticed a theme arising in what I’ve been writing about, which is being overpowered. Well, I’ve also been writing some heartbreak and breakup songs, which is odd, ‘cause I’m not really in any kind of breakup situation. I think people I know are just breaking up a lot — I guess they always are — and I was listening to a lot of breakups.

I got so into Joanna Sternberg this year. They made this album that came out this year called I’ve Got Me. This is the kind of thing that really gets me to write more than anything else: I hear some music and I’m like, “Shit! I forgot that there’s more, that there’s further to go, that it can be this good.” I’ve made my attempt at making my version of what I think is good music, and then I hear somebody who does it so much better.

That makes me think of the way you talk about Alex Walton’s music.

I’m obsessed with her music ... I felt like a fraud after performing right after her. I was like, “I gotta come up with something better.” She had this whole film playing behind her. It was incredible. She makes me jealous. We do write very different kinds of songs — she had a great term for the kind of writing I do. She called it “one-level metaphor.” [Whereas] she’s just taking her life and thoughts and putting it into the song. It’s hyperconfessional, brutal, overwhelmingly sincere, as she put it. To me, her music is kind of like rap music. It’s a lot of talk-singing, but when there’s also a melody, you could put anything into those chords.

I feel embarrassment sometimes about my own one-note melodies. My bandmates used to kinda make fun of me, like, “Oh, that’s another three chords and two notes that you’re singing.” But even before they were making fun of me about it, I was jealous of melody writers. I remember this thing that, in retrospect, has had a huge influence on me — this one comment that Paul Simon said in an interview, which was like, “The age of melody has passed ... Melody used to be the guiding thing for composing music, and now we’re in the age of rhythm. And people don’t write good melodies anymore. Paul McCartney’s one of the last melody writers.”

And I was like, “Fuck you Paul Simon, I can write a melody!” This was when I was still in college, I think. I started to really think more about melody back then, and maybe it’s been a huge distraction. Sometimes I’m like, “I’ve been wasting my time with melody,” just from hearing Lex, the places that she has found with just stream-of-consciousness confession. And I feel that way about great hip-hop and rap music. I listen to Nas and Boogie Down Productions, and I’m like, “Man! And I call myself a lyricist.” These people are so much better. Kendrick Lamar — he’s doing wild things with storytelling and character. I’m playing in the sandbox compared to these lyricists.

How does being trans influence your music, if at all?

They say one thing that creates cool art sometimes is when people are rattling or bending the social bars that cage them and can’t really keep them in. Getting free, whether we know it or not, is often what we’re drawn to in art, I think. When you can hear someone who’s not fully free and not fully suppressed but is transitioning from one to the other, that’s exciting. When genres are born, they’re usually started by people who are getting free. When they get boring, they’re by people who’ve already gotten free.

Trans people right now, we’re breaching a social threshold of some kind. I think trans people actually have always been breachers in that way, so we usually have made interesting art. I think we’re less effectively suppressed than we used to be, and that’s causing us to be heard more, have more resources to make stuff, and have less disincentive to be seen in public, and all that stuff helps. I don’t want to be one of those people who says, “Oh, art is better when the performers are suffering,” because I think it’s worse. But there’s always some threshold to breach. There’s always some way to be born — some vagina you can only barely squeeze through. And I think a good art comes from squeezing through a new vagina.

Has making music influenced your identity? How did it influence, if it all, your transition or anything like that?

It’s very hard to tell, honestly, ‘cause ... I made friends with these indie rock bros. That was how I started a band. I’m not clear on how true this still is among 19-year-olds, but women weren’t really in bands around me. So I formed a band with these bros and then that band eventually broke up. I formed a band with more bros. So it was just bros. Bros, bros, bros. I love my bro boyfriends. I love all those people that I’ve been in bands with, but I do kind of wish I was hanging out with more women, with more queer people. In college, I didn’t know about being trans. I’d never heard of that until senior year of college, which is a drag to think about. ‘Cause I was trying to do it. I was “cross-dressing.” I sometimes think this bro-y indie rock scene kind of slowed me down.

But, then again, I first appeared feminine in public on stage. And I had that as a place to try it out. I had plausible deniability, you know what I’m saying? So it was the cradle of trying things out, but it also always bugged me that there was a period in which I had started to look feminine kinda regularly offstage, and people still thought it was a stage gimmick. Like, “That’s what that person does when they perform.” People always invoke David Bowie to me in a way that pisses me off.

I would not make that comparison.

I know, I don’t really understand. We don’t have a lot in common. It would bug me that people saw it as, “Oh, you’re experimenting.” I think I got a little distracted by that for a long time. I think it kind of slowed me down that people were reacting to the way I looked, in this way that was like trying to encourage my liberation but it wasn’t actually the liberation that I was [looking for] ... I spent a long time just being like, “I’m not trans and I don’t care about these labels. I don’t choose one, it’s all fluid, I just do whatever I want to do. I’m free and I wear whatever I want to wear and categories don’t apply to me.” It just wasn’t the most helpful thing. It took me a while to get past that and say it’s kind of important to name and embrace transness as a thing that I do claim.

I think it also influences my music. It’s a part of an effort to be for real, which I think is what I was talking about when I said the hustle is a distraction, the career is a distraction. Something I read that was a big influence on me was a biography of Leonard Cohen called I’m Your Man by Sylvie Simmons. I really get the sense from reading about his life that he was doing not only multiple kinds of art as one project, but things that weren’t art also. His whole life just looks like one spiritual project to bring out the truth of his humanity. That includes writing poems, writing novels, writing and recording music — that’s the art side. Then it also includes spiritual exploration, meditation, and doing Judaism. It was all one thing. That’s how I like to think about my life, basically. Everything I’m doing, you can think of it as having a unified purpose, which is just to be the person I want to be ... to give my soul its actual expression. Manifestation in reality. To not only live in private, in the inside of my head, but to live in the world and make the stuff inside me real in the world. It’s a little overly lofty maybe.

Do you think you’re gonna be all done with the pseudo-residency after April?

I don’t know. I truly don’t know. I almost didn’t do it because I have this feeling everything has to be special and different. I know there’s repeat audience members, and I get self-conscious about it. I’m like, “Why aren’t I doing something stunning with this?” It’s just like a poetry reading with guitar chords, I’m just reading my texts. Some people do amazing things, you know. “Theater.” The whole time, I’ve been wanting to duet with people, and I barely have done that.

I loved your and Alex’s rendition of “Candy Says.” It’s such a good song.

It’s one of the best. It’s my favorite band.

What are you doing outside of music right now?

I’m glad you asked. I finished a full draft of a book-length thing and I gotta figure out how to put it out. It’s a memoir plus readings of the Bible and other Jewish texts. I’m working on the elevator pitch, as you can tell ... it’s a strange in-between genre. And I’m not sure who it’s for, but I feel like it’s good.

// Journey Whitney ’24 (any/all pronouns) is a staff writer for Record Hospital.