WHRB Sits Down With The Zombies

Listen

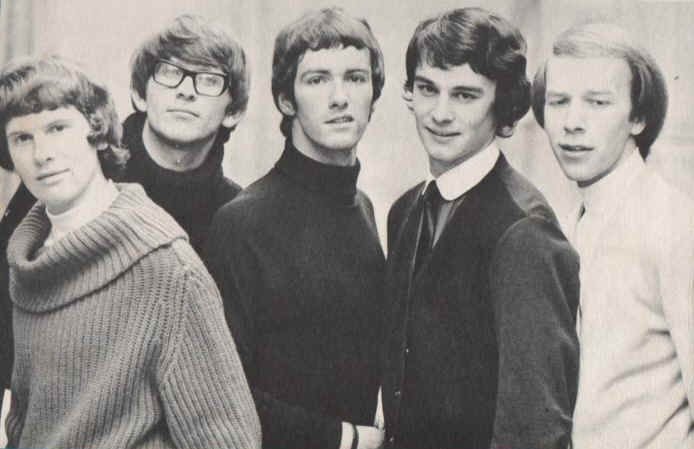

Along with the Beatles and Beach Boys, the Zombies are regarded as the greatest melody and harmony writers of the 1960s. They are best known for hits like "Time of the Season" and "She's Not There," and they continue to perform and release new material. On March 10, 2017, WHRB DJ Alasdair MacKenzie interviewed Rod Argent and Colin Blunstone of the Zombies, who have been the keyboardist/vocalist/songwriter and lead vocalist, respectively, for the band since the early 1960s. The main topic of discussion was the Zombies’ 1968 album Odessey and Oracle, which the band is currently promoting with a 50th-anniversary tour. The Zombies will be performing at the Wilbur Theater in Boston on Tuesday, May 9.

PART I: Rod Argent

Alasdair MacKenzie: Let me get the gushing out of the way -- can’t promise it won’t come back -- but I got Odessey and Oracle for Christmas when I was thirteen years old. I’m nineteen now, and I’ve never stopped listening to it, never stopped showing it to any of my friends who will listen to me rant about how much I love it. So thank you for creating art that has definitely changed my life in a positive way. I love that album so much, and your other work, too.

Rod Argent: Thank you so much; it’s lovely to hear that. I mean, one of the things that just knocks me out continually is that we do seems to be able to relate with that music to a current generation, as well as people who have followed us all the way through. That was unlooked for, and it’s fantastic.

AM: When you made the album, did you see it as superior to or different than the other work you’d been doing? Or was it just another batch of songs that it was time to record?

RA: It was another batch of songs, but just before that recording, we’d become very frustrated with how some of our recent singles had been produced. We felt that they didn’t have the right perception of harmony; we felt that some of the balls had been taken out of what we were playing, and Chris and I, who were the two writers in the band, were really keen that we should be able to get our own ideas of how our current songs should be sounding onto record. That’s why we went to CBS or Columbia, and said, “would you give us some money,” which they did -- not a lot, I have to say -- ”to record an album the way we want to record it?” But then, having said all that, they [the tracks on Odessey and Oracle] were just the songs we were writing at the time.

AM: Your first two hit singles -- ”Tell Her No” and “She’s Not There” -- were produced by Ken Jones. Was he the one who was producing you up until Odessey and Oracle, or did you go through different producers?

RA: No, it was always Ken Jones. Now, I have to say that Ken was a great musician, but he was from a previous generation--the previous generation to us--and he didn’t dislike rock and roll, but he came from an era that thought that you had to concentrate on a gimmick. So, for instance, we loved his production on our first session, from which “She’s Not There” came, and on that first session, we recorded “She’s Not There,” “Summertime,” the song that I wrote before “She’s Not There,” which is called “It’s Alright with Me,” and a Chris White song called “You Make Me Feel Good.” We loved the way all of those turned out, but what he was doing at that time was just making the best of the material that we were presenting to him. After that, he was trying to analyze what made “She’s Not There” a hit, and in his head, it was Colin’s breathiness on his vocals. Now, I love the breathy quality of Colin’s vocals on “She’s Not There,” but that was only one of the things that made it a hit, and [Ken Jones] sort of self-consciously tried to emphasize the breathiness of Colin’s vocals above other things on subsequent records, and it was driving us mad. He was a very autocratic producer, actually; he never used to let us go to the mixes, for instance. But when we actually got to the point where we said, “look, Ken, we want to produce an album ourselves,” he said, “fine.” He said, “I’ll help you,” and he helped us get Abbey Road, and to my knowledge, we were the first band outside of being an EMI artist that were allowed to record at Abbey Road, so hats off to him for that. And he was a lovely guy, and just a very autocratic, old-school producer.

AM: That makes sense. I think the notion of producer-artist collaboration was a thing that was pretty new when you guys were making music.

RA: It really was. I watched Eight Days a Week the other night on my iPad, the Ron Howard film [about the first several years of the Beatles’ career], and you can see how [Beatles’ producer] George Martin, in the very early days, said that [autocracy on the part of the producer] was the relationship. The producer was a demigod; he called all the shots, and it was only as the pop landscape changed that the Beatles started to have more input, and an artist’s idea of how a record should sound -- their own record -- was valid. You’re absolutely right; it was a pretty new concept at that time.

AM: What about dynamics vis-à-vis arranging and making recording decisions about a particular song within the band? I know you and [former Zombies bassist] Chris White were the primary writers. When you brought in “Care of Cell 44,” did you have the drum part written or in your head, the guitar part written, or was it that [former Zombies drummer] Hugh Grundy wrote his own guitar part, [late former Zombies guitarist] Paul Atkinson wrote his own guitar part, and it was a democratic process? On that spectrum, what was the arrangement process like?

RA: I think that Chris would say the same thing as me; I’m not being arrogant when I say that, generally speaking, I used to be in charge of the arrangements, and the arranging of the harmonies, too.

AM: Even on Chris’s songs?

RA: Yes, to some degree, although, obviously, it was an equal relationship. Obviously, I took a huge amount of notice of Chris’s ideas. I’m not saying that Chris didn’t have a huge input into things, but, for instance, the very first record we ever made, one of the first songs I ever wrote, was “She’s Not There,” and one of the first things I wrote about “She’s Not There” was the bass line (sings bass line), and the drum part, the broken drum part (sings drum part). That was written; that was integral to the song; that was part of the writing of the song, and I arranged all the harmonies on that song, for instance. Now, on Chris’s songs, let me see if I can make a couple of examples--

AM: Like, who did the vocal arrangement on “Changes” [written by Chris White] on Odessey?

RA: It was basically me, really, although Chris would very possibly have said, “I think this is a choral thing, and let’s hit a big choral harmony at the beginning,” but it was generally me that would say what the notes were. And then, for instance, we rehearsed “Changes” assiduously, but we had some extra multi-track recording facility when we did Odessey and Oracle that the Beatles had developed in the previous album -- which was Sgt. Pepper -- to us going in there. [The Beatles recorded Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band at Abbey Road Studios in London, where the Zombies subsequently recorded Odessey and Oracle.] Because of that, on “Changes,” we put down what we’d rehearsed, and then, in the studio, I heard in my head that little counterpoint line on the top (sings line), and I said to Chris, “I can hear something,” and I sang it to him, and he said, “yeah, get in there and do it.” So I just threw that in; that was like a spontaneous thing, really. But generally speaking, I would arrange the harmonies. I’m not saying I told Chris exactly what to play on everything. Of course I didn’t. And I didn’t tell Hugh what to play on everything, but when there was a little part, I would often throw that in. On “Beechwood Park,” for instance, another great song of Chris’s, he came with the completed song, of course -- with all the chords, and the melody, and the lyrics -- and I loved it. But not that long before, Procol Harum had come out with “Whiter Shade of Pale,” and I said to Chris, “you know, it would sound great if we got some of that mood.” I don’t mean copy what “Whiter Shade of Pale” was, but with a slightly baroque line. So that little guitar line, (sings line) that was me that put that in. So that just gives you a little idea. But it was collaborative, though. I’m not saying I nailed down all the notes, and everything, cause I didn’t. It was a very collaborative thing, and everyone had their input and had terrific ideas, too.

AM: Some of my favorite moments on the album are little vocal riffs that Colin [Blunstone, Zombies co-founder and lead vocalist] does. Like, on “This Will Be Our Year,” the last verse: “the warmth of your smile, smile for me, little one”--the way he goes up and deviates from the previous melody there. Was that a spontaneous call by Colin, or was that you or Chris directing him, there, or how did a moment like that come to be?

RA: I can’t remember, but I would think that that line you’re talking about would have come from Colin.

AM: Okay, so it was very collaborative, and a lot of the moments are attributable to different people.

RA: Absolutely. And Chris and I, whoever had written the song, were very open to something that was done on the spur of the moment that sounded great. If Colin through something in that was a bit different to what was written, and we loved it, we’d say, “that sounds fabulous, Colin.” Absolutely.

AM: When you were arranging vocals, was there anybody in particular you were thinking of? I’m just asking because I know that Brian Wilson [of the Beach Boys] owes a lot to the Four Freshmen, or the Beatles owe a lot to the Everly Brothers, but I don’t see as clear of a pop-world antecedent to the Zombies’ harmonies.

RA: The one thing I will say is that I never thought of things just in parallel. Very many very good harmony groups would always take a melody, and someone would take the root note, and someone would take the fifth, and someone would take the third, and they’d go as far as possible in parallel. Now, the Beatles didn’t do that. They, intuitively, used to do more imaginative things.

AM: Right, like “This Boy” or “Yes It Is,” very interesting arrangements.

RA: Yeah, I can’t think of any examples at the moment, particularly, but I’ve often thought of the Beatles, “oh, that’s great, the way they do that, and the interval that they’ve used there, and the way the two voices move against each other.” The Beatles were just, intuitively, so creative, just fabulous. The thing is, I always loved music, but for the first ten years of my life, I only really liked classical music, ‘cause I didn’t like much of the pop music that was around until I heard Elvis sing “Hound Dog,” when I was eleven years old. I was in a great choir; we used to broadcast on the main classical program; it was a cathedral choir, and it opened my ears to a huge amount of fantastic music, spanning many centuries. It also gave me an intuitive feeling of being amongst some of the best harmony lines ever written. All I’m saying is that it was a privilege to just have that going on around me for several years, and that really helped my intuitive grasp of harmony. Arranging harmony has always been very easy for me; I can see it immediately, really.

AM: Would you write arrangements out on sheet music paper, ever, or would it all be taught by ear?

RA: With the Zombies, at that point, we’d always do it ‘round the piano, and I’d say, “Chris, you sing this line.” Very often, what we would do -- Colin thought this was highly amusing, and he’d tell you the same story -- but, for instance, on “She’s Not There,” Colin would sing the melody line. I would then give Chris a line that was as close to one note as possible, and then I would leap around that, to fill in the other notes, and so sometimes, my harmony lines sounded very bizarre, indeed, when you heard them just by themselves, but when everything was all going together, it sounded natural.

AM: This is a revelation that came relatively late in my Zombies fandom, but you sing a fair number of the songs on Odessey and Oracle, correct?

RA: I sing “I Want Her She Wants Me,” and I take verses in things like “Brief Candles,” and I do the middle of “A Rose For Emily.” People often ask us how we keep our chops together, and I started taking vocal lessons, not to change my voice, but just to strengthen it, really, around the eighties, sometime. It was after I made a solo album, actually, and I was really disappointed with how my voice sounded, and I worked on it, and I really think my voice is in a different place, now. I think it’s far, far better than it was when I was young. I can sing higher; I can sing stronger, and it’s got more fullness to it. So I’m not particularly proud of the actual sound of my lead singing on Odessey, but it works within the context of the songs, I think.

AM: I think it’s wonderful! I thought it was Colin; I didn’t know that you sang at all until I read the liner notes. It sounds very in the style. Two of my best friends in high school and I all got into the album around the same time, and then one night, one of them read the liner notes and texted me, “wait! Did you know Rod Argent sings “I Want Her She Wants Me?” And I said, “no, that can’t be true! Impossible!” I think it [different singers in a band sounding alike] probably is a thing that comes from singing together so many years.

RA: I think that’s right.

AM: You just assimilate the other person’s style. I hear it in the Beach Boys; I hear it in Simon & Garfunkel. There are little moments where everybody converges.

RA: You’re absolutely right. That does happen in many situations, yeah.

AM: Like we’ve talked about a little bit, way back at the beginning of our conversation, the Zombies have had a considerable amount of influence on the modern pop/rock/indie--whatever you would like to call it--world of music. Are there any particular songs or bands or albums, say, in the last decade, where you can hear the Zombies’ influence? And do you like or dislike or have an opinion on what they’ve done with the legacy of your music?

RA: I can never hear it. I honestly can’t. Many times, people have said, “oh, we were so influenced by the Zombies,” and I could never hear it. I don’t know what it is. I didn’t listen to Odessey and Oracle for years after it came out, once it hadn’t sold initially. As you probably know, about ten to twelve years after it came out, it did start to sell.

AM: It didn’t even sell when “Time of the Season” became a hit in the late sixties?

RA: No, [Odessey and Oracle] didn’t. Can you believe that? It [“Time of the Season”] was #1 in the Cashbox charts, #2 or 3 in Billboard. Cashbox was an absolute equivalent, at the time. So we were top of the American charts. The album made the top 100, but it didn’t get very far up.

AM: That’s not very much compared to a #1 single, yeah.

RA: I know; that’s crazy. It sells more every year now, than it ever did when it first came out. Year in, year out, now, it has steady sales, which is fantastic. I know, to some extent, that was true of Pet Sounds [1966 album by the Beach Boys], as well, but it sold a lot more than Odessey did. [Odessey and Oracle] didn’t sell very much, at the time, at all. After it didn’t sell, I didn’t really listen to it for about ten years. We loved how it turned out--got great reviews--but it didn’t sell, and then I stopped listening to it. And then, when I did--after about a twelve, fourteen year period, I went back and listened to it again--it just sounded like us. All I can hear is us singing it and playing it, and I can’t hear it objectively; I honestly can’t, so maybe that’s something to do with it. I’m very flattered that people feel that they did base so much on it, but I find it difficult to hear those things.

AM: That’s really interesting. I think there are lots of bands, lots of people who I think see it as part of the same canon of melodic, harmonically rich music as Pet Sounds, or as Sgt. Pepper, or stuff like that. It’s probably absorbed all as one with those things, would be my guess.

RA: I think it was a moment in time, and I think it was a great time for music. Maybe that’s just my age talking, but I think for all sorts of music, it was incredibly positive and creative. What was very progressive at the time was embraced by the listening audience. It’s not like today. I think that the Beatles, again, had a lot to do with it. I think they were the first progressive group, because they always wanted to stretch to boundaries, whether they were boundaries of sound, or recording technique--backwards tape. They had a lot in common with avant-garde classical music, at that time, in their approach to what they were trying to do and their curiosity about what you could do with sound and how you could develop the structure of songs. And of course, Brian Wilson had that, too. We hadn’t heard Sgt. Pepper when we started to record Odessey, because we just followed them into the studio, but we certainly had heard the precursors to Sgt. Pepper, like “Strawberry Fields Forever,” and we’d heard Pet Sounds and been knocked out, particularly with Brian’s approach. It was revolutionary. It was really a mature, progressive way of looking at what you could do with a pop song, and not ruling anything out. I know it took a while for people to accept Pet Sounds, but people were open to things. It was a fantastic time for music, and we were around at that time; we couldn’t help but be affected by the spirit of the times.

AM: Are there any moments on Odessey or in any of your music at all that you can point to and say, “if not for Brian Wilson or if not for the Beatles and George Martin, that Zombies moment would not exist?” Can you think of anything like that on Odessey?

RA: No, I can’t, actually, because there was not a single instance where we copied a voicing, or a...it was just really the general approach to things. I’ve already mentioned to you, when I wrote -- in our very first session -- ”She’s Not There,” I was very interested in bass lines, and I wrote that bass line, and there were a couple of instances where I would often play a different bass note to the chord in what I’d composed. On “Care of Cell 44,” for instance, on the chorus, when we sing the “oohs” or “aahs,” [sings], that bit. Basically, the two chords I’m playing are G to C, and in the bass, I put a G bass note. And then, over G to C, I put an F bass note.

AM: Right, or in the bridge you have the G to A to A-flat to G, with G in the bass the whole time.

RA: Yeah, yeah, things like that. The melodic nature of the bass always interested me, and in 1964, as I’ve already said to you, I wrote that bass riff right at the beginning of my writing of the song. Now, that’s something, to some extent, that the Beach Boys used to do, particularly when they moved away from the surf music time.

AM: It seems like you almost got there before them, with “She’s Not There.”

RA: Well, maybe, with “She’s Not There,” I did, but it was something which Brian Wilson naturally felt. But he took it to another stage on Pet Sounds, and that really knocked me out, the composition of the bass lines around what was going on. That definitely made me want to take what was natural to me, anyway, and concentrate on it a bit. You’ve got the opening of (sings opening passage) “Care of Cell,” and in several places, there was a particular melodic bass line that I asked Chris to play. I’m not saying I told him what to play on everything, as I said before, because I certainly did not, but there were certain instances where I said, “it would be great if you could play this melodic line.” I don’t think that would have happened if it hadn’t been for Pet Sounds. I think it just excited me more to say, “oh, I love the way he’s doing that,” and it’s something which felt natural to me, anyway, and I wanted to develop that more myself. I think you can see that, to some extent, on Odessey. I’ll tell you what: to coincide with this tour, BMG, who’ve taken over our new recordings, now, have released a coffee table book, which, I have to say, they’ve done a fantastic job on. We’ve done handwritten lyrics for each of the songs on Odessey, and other songs, too, and anecdotes, and artwork. BMG have got together endorsements and quotes from some fantastic people, and it completely knocked me out. I had no idea they were getting these people to talk about us, and there’s a quote from Brian Wilson at the beginning, saying, “I loved the Zombies’ harmonies,” and “who could forget their early singles; I liked them immensely.” I can’t remember the actual words, ‘cause I haven’t got a copy at the moment; I’ve just seen it, and I was so knocked out to see those things. Graham Nash, who came to see us last year, said, “I saw them last year, and I was mightily impressed.” That thing about Brian saying such nice things about our harmonies, I don’t think it gets much better than that in a pop context.

AM: No; if Brian Wilson said nice things about my music, I would be ready to stop forever! I would have achieved my peak. Unfortunately, Rod, I’m all out of time, but thank you so much for being with me and answering my questions, and I can’t wait to see you guys in a couple weeks in Boston.

RA: It’s a pleasure, Alasdair. Thanks so much.

• • •

PART II: Colin Blunstone

Alasdair MacKenzie: One thing that strikes me about your music -- especially on Odessey and Oracle, but also in your solo career, also on other Zombies music up to the present day -- is your very unique singing voice. You’re breathy and light in a distinctly un-rock-and-roll kind of way. It’s very angelic and airy and ethereal, and it fits the Zombies’ music so well, but it doesn’t seem to come from Elvis or Carl Perkins or blues singers, so I was wondering where you got that from.

Colin Blunstone: I think that, for most singers, your voice is what you’re born with, really. Of course, you can strengthen it, and you can, hopefully, make it more accurate as time goes by, but the basis of a voice, I think, is what you’re born with. I was influenced by a lot of the rock and roll greats when I was younger, like Elvis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry; I loved all that music. But by the time we got to actually being a professional band, I don’t think I was really that influenced by anybody. It’s just what came naturally. In fact, if I was influenced by anybody, it’s by Rod Argent, [Zombies keyboardist and co-founder] because he had much more of an idea about phrasing, when we were in our teens, than I did. I was a very naive singer. I had quite a good voice; it was quite a strong voice, but I had no idea about phrasing, at all, and Rod certainly set me on the right way with listening to what I was doing, and just trying to help me get things a little bit more in order when I was trying to phrase a tune.

AM: This is funny: I was just talking to Rod a couple minutes ago about how I think his singing on Odessey and Oracle sounds like he’s trying to be you.

CB: Really! Maybe it’s a little bit of the other way around. The other thing is that we just grew up together. We’ve been playing together, off and on, since we were fifteen, and I don’t know if he said it to you, but Rod, in the past, said to me that he self-consciously always thinks of my voice when he’s writing a song. And, in the same way, I’m probably thinking about all the things he’s told me about singing when I perform a song. We work off of one another, I think.

AM: How many years of playing music together is that, now? That’s sixty?

CB: Well, we actually first got together in 1961, so it’s fifty-six years. But there’ve been gaps, when we’ve been working on different projects, but Rod produced or co-produced quite a few of my solo albums, and I’ve sang on quite a few of his projects, and whenever he does a charity gig, we always get together and play together. In 1999, we got together and formed the present incarnation of the Zombies, although we didn’t use that name then, so we’ve been playing all the time, very consistently, since 1999, so that’s eighteen years, there. And the irony is that the original Zombies were only actually professional for three years; though we played at school before that, we were only a professional band for three years. This incarnation of the band has been a professional band for getting on twenty years, now, so it’s quite strange.

AM: Has one been more fun than the other? Do you enjoy the stability now, or did you enjoy the craziness of the sixties, or something in between?

CB: I think they were both great fun. In some ways, there’s an added something with this band, because it’s so unexpected. Neither Rod nor I thought that we’d be touring at this time in our lives, so it’s been a surprise, but it’s been a wonderful surprise, that we can go out and play the music we love with our pals, and just go around the world doing what we love to do. It’s really taken me by surprise that there’s so much interest in the Zombies’ repertoire. Neither of us thought that that was true, and we’ve found over the years that there is a huge interest in the Zombies, and that enables us to tour in the Far East and in America, Canada, and all the way through Europe. If you’re a musician, all you want to do is play, really, and we’re being allowed to do that, so I think we’re very, very lucky and fortunate guys. It’s funny, because I think Rod is more of a glass-half-full person, and he always concentrates on the positive, and I have to admit, I’m embarrassed to say, but I’m a glass-half-empty person, so I concentrate on the negative. But, overall, I have to admit, even as a glass-half-empty person, we have been incredibly fortunate, overall. There’ve been some challenges and some difficulties, but I think we’re incredibly fortunate.

AM: A couple more questions about your voice, before I venture to other topics: One of the things that strikes me about Odessey and Oracle is that it’s in a genre of music that was made by, I’d say, you guys, Simon & Garfunkel, the Beatles, the Beach Boys, in the mid and late sixties, that really is departing from the roots of rock music. So, not a lot of blues, not a lot of country influences. But your vocals, at certain points -- I’m thinking of stuff you do on “Hung up on A Dream” or “This Will Be Our Year” [tracks on Odessey and Oracle] -- it sounds like you were listening to a lot of American soul singers, is that right? When you go, “my, my, my” at the end of “This Will Be Our Year,” or some of the riffs you do. Sam Cooke, or something. Is that true?

CB: Of course, I had listened to them, and you will be subconsciously influenced by these people. I mean, someone like Sam Cooke, what a wonderful singer. Ronnie Isley and the Isley Brothers, one of my favorite singers of all time. Marvin Gaye -- Marvin Gaye’s a little later, but all these wonderful singers, of course we were influenced by them. And, in fact, we toured with some of them in the sixties. The Shirelles, and Dionne Warwick, the Ad Libs, the Drifters. We toured with lots of black acts and were incredibly influenced by them, absolutely. And we were listening to the records of the Miracles and all of the Motown greats, even in the sixties.

AM: Did it occur to you, when you were incorporating those influences into your singing, that you were doing what seems to me like a very cool, original merger of very old, orthodox, white classical music -- which seems to be a big influence on Rod’s writing--and more modern, more culturally diverse soul music? Did that occur to you, or was it just that you were doing what came naturally?

CB: I think it was more just doing what came naturally, and to be absolutely honest, especially in the sixties -- I don’t really worry about this so much now -- I think I tried to sing with an English accent. A lot of British artists sing with a mid-Atlantic accent.

AM: I’m thinking of Mick Jagger.

CB: He’s a prime example, but there are many others. I was listening to Odessey and Oracle late last night, and there are a couple of words on there, where I sing them in a very English accent, and that was on purpose, because I just felt--this is just me, personally; I’m not criticizing anybody else--it just seemed more honest to sing that way. But it’s quite interesting that you’ve noticed a few little soul inflections gleaming in, because I was actually trying to sing it in an English way. And the fact that it isn’t particularly blues-based is really down to Rod and Chris [White, former Zombies bassist]’s writing. I think they were in a very rich vein of writing in 1967, and I think every song on the album is just a classic. As a band, we followed their writing.

AM: You, Paul Atkinson [late former Zombies guitarist], and Hugh Grundy [former Zombies drummer] don’t have any writing credits on the album. Does that mean that you were also mostly not party to the arrangement decisions, or was that more democratically distributed than the writing? Like, did you come up with the vocal inflections that you did, or any vocal arrangements, or was that mostly up to the writers?

CB: To be absolutely honest, I think it was mostly up to Rod. Even on Chris’s songs, Rod would usually be in the MD seat; he would be the musical director, if you like. We all referred to him. I mean, there would be natural things that I would do, but, especially just thinking about the lead vocals, Rod and I would always go over the phrasing of the songs. I would never go into the studio and just sing a song without we discussed the phrasing first, and that’s still true now. When we do songs now, in the present incarnation of the band, usually, Rod and I will get together ‘round the piano for a few hours--the guys won’t be there, just Rod and I--and we’ll go through the phrasing of the song. And when we feel we’ve got somewhere--and, to a large extent, that’s Rod coaching me--then we will take it to the band. A lot of singers want to do it their way, but for Rod and I, it works that way. I know that his knowledge of phrasing is really, really good, so I’m really pleased to work at it with him, and it’s helped me on other projects, when Rod’s not involved, because, in the process of singing his songs and Chris’s songs and going through the phrasing on those songs, I’ve learned a bit about phrasing myself. I was a very naive singer as a teenager. I had no background as a singer, even when I joined the band, when it was an amateur band. I joined as the guitarist, as a rhythm guitarist.

AM: I never knew that.

CB: Yeah! The very original bass player was a guy called Paul Arnold, but he left before we started making records, and Chris White took his place. Paul Arnold and I were at school together, and Paul had a friend called Rod Argent -- there’s no way I could have known him, ‘cause he went to a different school -- and they talked about forming a band. So Paul Arnold said to me, “you’ve got a guitar, haven’t you?” and I said, “yes.” And that was my audition; I was in! I just had to have a guitar. So we went to the first rehearsal, and Rod was gonna be the lead singer. We played an instrumental with lead guitar, rhythm guitar--myself--and bass, and Rod was just watching, ‘cause he wanted to be a rock and roll band, and he thought rock and roll meant three guitars. In a break, he went over to a broken-down, old upright piano, and he played “Nut Rocker” by B. Bumble and the Stingers, which was a hit of the time, and it was based on a classical piece, and I was absolutely amazed that, even at fifteen, he was a wonderful keyboard player. I’d only just met him, and I said, “you have to play keyboards in the band,” but he was quite reluctant, because he wanted it to be a rock and roll band, and he wanted three guitars. A bit later on, I was just singing in a corner to myself, and he heard me. I had no aspirations to be a singer; I was just having a bit of fun, and he said, “I tell you what: if you will be the lead singer, I’ll play keyboards in the band,” and that is how the Zombies came together.

AM: Wow, that’s such a nice, symmetrical story, that you guys discovered each other’s best talents.

CB: Very quickly, and so much of it was by chance. There may not have been a piano there, so he wouldn’t have played keyboards. I didn’t know he could play keyboards, ‘cause I’d only just met him. And he didn’t know I could sing, because neither did I! I had no musical background, at all, really. My family were quite musical, but they were musicians in their own right; they didn’t coach me, and so I came to it very raw. Rod had been a chorister in St. Albans Cathedral for seven or eight years, so his knowledge of harmony and phrasing was quite sophisticated, even at fifteen. Luckily, I’ve learned from him.

AM: I’ve heard tell that, in the recording session for “Time of The Season,” you and Rod went at each other a little bit; there was a little bit of discord about how you were singing the song. Is that true?

CB: Absolutely. It’s absolutely true. I must, first, say that “Time of The Season” was the last song to be written [for the album], and it was finished in the morning, before we went into the studio, to record it, in the afternoon. I would be the first one to say that I didn’t really know the song. We were doing our coaching process, but we were doing it with Rod in the control room and me in the studio, and, of course, he had all the Abbey Road engineers ‘round him, and the rest of the band, so it wasn’t as if we were doing this in private, and he was trying to lead me on the phrasing of “Time of The Season.” I was struggling, because I didn’t know the song. Also, we were running out of money; we had a very tight budget. So, the red light’s on, the clock’s ticking, starting to panic, here, and I said to Rod, through the intercom, so everyone else heard, “listen! If you’re so clever, you come in here, and you do it!” And he screamed back at me, and he said, “you’re the lead singer! You stand there until you get it right!” To me, the funny thing is that, at that time, I’m singing, “it’s the time of the season for loving,” and we are absolutely screaming at one another, and, I have to say, the language was probably pretty colorful, too. But I did stand there and get it right, and I’m really glad I did, because that record went on to sell nearly two million copies, so I’m really glad that we managed to get there in the end.

AM: I have to say, for the most fabled, heated disagreement to happen in the Zombies, it seems like a remarkably ego-less disagreement, too. Rod could have said, “alright, you’re not cutting it. I’ll come and sing it,” or you could have demanded that you be given more chances, but you were both pushing in the direction of the other person, which I think is indicative of a very cool dynamic.

CB: We’ve always been like that. We only want what’s best for the project, and that’s true today, with this band, the present incarnation of the Zombies. We just want the best songs and the best performances so we can be proud of what we’re doing. That’s our motivation, really.

AM: When you’re observing music now, do you hear other bands, or other artists, or other songs that seem to you to be influenced by your music? I’ve heard a lot of bands talk about Odessey and Oracle, and the Zombies in general, as one of their guiding lights when they’re creating. I was wondering if you hear that, too, and if you have any thoughts about what people have done with your musical legacy.

CB: It’s very exciting that so many artists do cite the Zombies as an influence. I’ve got to be really honest and say that I rarely -- very rarely -- actually hear it in other artists, but it is wonderful to think that, somewhere along the road, our music influenced them and hopefully excited them and helped them to go on to what they’ve become. But rarely do I ever literally hear it. I can’t even remember one instance where I’ve heard it.

AM: Regardless of their influence or lack of influence from you, are there any bands that you hear right now that excite you?

CB: My mind has gone completely blank, but if I can just talk in general terms -- whenever I’m trying to think of artists, I can never really think of anyone -- there are a lot of wonderful singer-songwriters around at the moment, and I’ve been really excited by some of the songs that I’ve heard from these singer-songwriters, male and female. When I do interviews at home, I’ll have a list of artists -- I’ll write them down -- so that I don’t come up with a blank when I get this question, but I think that’s the area that I’m excited in. I don’t think there are really bands that are really exciting me at the moment. It’s the area of singer-songwriters that, for me, is where the future is.

AM: Single individuals with just a guitar or piano?

CB: I mean, sometimes they will supplement it with more of a band sound, but they are basically singer-songwriters. But you’re right; there are a lot of them that just play piano or just play guitar. Fantastic, absolutely fantastic.

AM: At the end of the song, “Friends of Mine,” you finish the music, and then someone -- I assume you -- goes, “ah.” What’s that about? Where did that come from?

CB: It is me, because, I just thought, “it’s a really lovely song; it’s a very sweet song,” and it’s just a little bit of irony at the end. You know: “ah, isn’t this lovely.” It was me, and I will do it on stage, as well.

AM: I can’t wait to see that. Thank you so much for talking to me, Colin, and have a wonderful day.

CB: It’s been fun. Thanks ever so much; all the very best.

~~

Alasdair MacKenzie is a DJ for The Darker Side on WHRB.